You undoubtedly came away from each painting session with thoughts and feelings about the experience. Whether you were consciously aware of it or not, recovery was in progress. To extend and expand the process, you may wish to pursue one or more of the following activities.

Keeping a Journal

In its very essence, journal therapy is a bridge into first our own humanity,

and then our own spirituality.

~Kathleen Adams

A journal can become a record of your experience, not necessarily (perhaps especially not!) for others to read, but for you to reflect on from time to time and be reminded of the changes that have taken place. During the process of writing, a journal provides a private, safe place to vent, dream, doodle and create. It is also—if you are willing to suspend judgment and simply write—a channel for amazing discoveries.

While journaling in the fall of 1995, I realized that I was writing in “small tight letters”. Over the next couple of weeks an occasional line of pure visual scrawl showed up on the pages. I started to write of wanting to make messes, to play, to “be loud on the paper”. Within two weeks, the sentence “Maybe I should be painting” spilled out. A month later, when the voice of my inner muse became even clearer and I was more comfortable with letting her have her way I wrote, “I’m getting too messy and it’s okay.” That day I penned three pages of large, graceful, flowing script.

While I’d been busy sorting through day-to-day events, a deeper level of consciousness was working to resolve problems I didn’t even realize I had. Call it the wisdom of God, Buddha, Muse, Universal Intelligence, Divine Intervention, Higher Power—whatever works for you—there is an inner essence that seeks and offers solutions on your behalf. It reaches out in dark-time through dreams, and in broad daylight through everything that is meaningful to you. One way to prompt and gain access to this internal wisdom is journal writing.

There is no one right way to journal. How much time you spend writing, the length of your entries, and the tools you use are entirely up to you. I’ve used a variety of materials and methods. All of them, without exception, provided me with what I needed at the time.

As for what to write with, keep it simple. I have filled nicely decorated hardcover journals but I always go back to Hilroy scribblers, the same type I used in school. They’re inexpensive and promote a more carefree, spontaneous approach to journaling. Keep a supply of your favorite pens handy. I use those that are lightweight and comfortable, preferably with black ink.

My personal guidelines for journaling are much like the ones I shared with you for painting. Settle into a comfortable spot that is free from distractions. If you have difficulty getting started, you might try jumpstarting your writing sessions by answering one or more of the following questions:

- How did the experience of painting make you feel? What did you especially like about it? What did you not like about it?

- What did you learn? Was there a moment of truth? Tidbits of insight?

- What would you like to tell someone about your painting(s)?

- What would you never tell anyone about your painting(s)?

- Which painting is your favorite? Why?

When writing in your journal set aside preconceived notions. Expect nothing, and everything. Play. Explore. Experiment. Go with the flow. If the events of the day or items for your grocery list come to mind, write them down. Doodle. Vent. Ask questions. Make wishes. Have fun. And if you’d like to kick things up a notch, try stream-of-thoughts writing.

Stream-of-thoughts writing

…drop a line into the pool of words around you…

~Susan Goldsmith Woolridge

This process begins with writing the first thing that comes to your mind, quickly followed by the next. Continue writing, not lifting the pen or your eyes away from the paper (or screen) but, instead, joining your rapidly-occurring thoughts in one long entry on the page. Set aside concern for punctuation and grammar, and allow the writing to lead you. Become willing to immerse yourself in a flow, or stream of thoughts.

A number of pages in my journal contain long, rambling lines of what many might consider pure nonsense. I see them as gems. Dark, light, whimsical, and just plain silly—they entertain and inform me. Within those lines I asked questions. I made wishes. And I gained insight.

On the following page is an excerpt from one of my journals (believe it or not, I was entirely lucid when I wrote it). It’s very long, and the lack of punctuation and grammar make it a difficult read, but I wanted to give you the best possible example of what can happen when you really cut loose.

“September 20th, 1995

Tired before I get going, messy, scrawly, scribble. Messy Molly. Jolly Jo? No Jo. Nope. Nope. Just me Somewhat the dope when I get these silly rhyming jigs I think of cats and toads and pigs and scribbly scrawly on my wall a sort of scribbly scrawly scrawl, letters all in disarray my thoughts are moving swift today and pen is sure a slippery thing a cartridge with a broken wing no flight of fancy just the grub of letters stuck in inkwell mud a lot of garble this and that a hose of ribbon copy cat no sense just me in lazy lines of words and page in two four time I like this scrawl it makes me free no bounds we know in poetry pure junk that often leads to gold in favorite quiet stories told whispered in my memory for only my eyes will see and isn’t that a stupid line cause I just broke rhythm for rhyme and now I’m off the lyric train to write my thoughts just lazily floating with pen and paper ashtray on table and trees through the window of a blue sky day in green and yellow coat no rain so far but warm sweater on just because I’m glad to be warm and will write more garbage till I feel it is enough and daydream of all the warm home feelings my eyes feel heavy, no not, just my arm in constant motion gaining ground from the mad movement of hurry rush garden of weedy thoughts pushing through flowers bold and brilliant no rain dry messy garble new books new thoughts work on letters and become wide awake birth projects this mad messy painting might be a Picasso in disguise as a literary agent a message of outpouring, taking out the garbage, only Picasso was brilliant and I am only a prairie poet writer of sorts with dreams and no painting experience, just words and emotions…”

Don’t feel badly if you either stopped reading past the first few lines or skimmed your way to the bottom. It is only hoped that on your way through you noted that my thoughts leapt from one thing to another, and that I didn’t stop to try to make sense of them. About halfway down I did become self-conscious and tried to control my word choices:

“…whispered in my memory for only my eyes will see and isn’t that a stupid line cause I just broke rhythm for rhyme and now I’m off the lyric train to write my thoughts just lazily floating…”

Did you catch this shift in focus and energy?

Did you also notice the rhyming in the top portion of my journal entry? Your entries may or may not contain rhyme but, if you follow the thread of your rambling thoughts, they will have rhythm. Certain concepts, feelings, people, places and things that are meaningful to you tend to catch your inner ear again and again, and will be echoed in your stream of thoughts.

Serious stuff may float to the surface, but please do try to have fun with this. Chances are, what you write will become even more meaningful to you later. When I wrote the entry above, I thought that I was merely purging. In retrospect I realized that my inner muse was trying to tell me I needed to loosen up, and that I might achieve this by painting.

Making the Most of Your Marks

A painting is never finished—it simply stops in interesting places.

~Paul Gardner

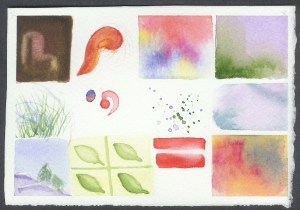

This section provides a few suggestions for taking your works to another level, if you so choose.

You may have decided not to pursue this particular form of creativity any further. Perhaps you are ready for something new, and that’s a good thing. Personal transformation/recovery involves getting to know who we are and what we want. Please, however, don’t make a decision not to continue painting based on anyone’s assessment (yours included) of your skill as an artist. Never buy into the notion that what you have created is not worthy of a second glance, or a second chance. We all make marks we’re not happy with. Treat your creations, like yourself, as precious works in progress. And get ready to be pleasantly surprised at what a little tweaking can do for your art, and your perspectives.

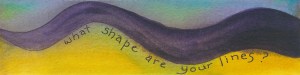

Text

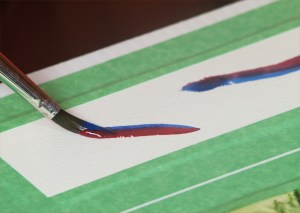

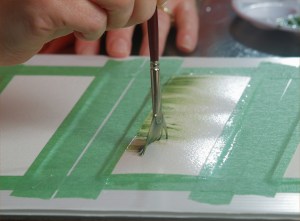

When working on your paintings, did you find yourself thinking, “this reminds me of…” or “this feels like…” or “this seems to say…”? Adding text to your paintings can personalize them by accentuating the emotional elements in your composition. There are a couple of ways to go about it.

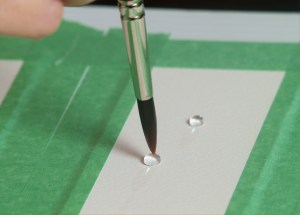

You may wish to add text directly to your painting by hand. This will be especially appealing if you have confidence in your penmanship. I do not, but tried lettering some of my pieces with black pigment liners.

Decide what you’d like to say. Keep it simple, and practice writing it out on a piece of scrap paper before committing it to your painting. Once you begin, there is no turning back. If that thought makes you nervous, mock up the letters on your painting with a fine-point pencil first. Just take caution to pencil in as lightly as possible. The pigment liners are smear-free but may lift somewhat along with the pencil marks, should you need to use an eraser.

If you are entirely uncomfortable with the idea of hand-lettering directly on your painting, but still would like to see it with text, consider taking your work into the technical arena.

Computer effects

Personal computers have taken the work of art into a new arena for both professionals and amateurs. I used a PC to tweak some of the paintings in the Dark/Light series. With the use of a scanner and a basic photo-editing program, it was quite simple.

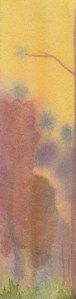

The painting for Meditation Week One is identical to the painting for Week Fifty-Two. It is, in fact, the same painting. With the click of a button, the lambent atmosphere of the original you see in Week Fifty-Two was transformed, and became the inspiration for the first meditation. The program I used was Adobe Photoshop 2.0, which was available online as a free download. Adobe has a number of more sophisticated editing programs, but this one was great to get started with.

Adding text with a computer is nearly as easy. The software for the all-in-one printer-scanner-copier I used while painting the Dark/Light series allowed me to add a title directly to the digital image. The length of the message was limited, however, because the text could only be applied in a single line. But with document software such as Microsoft Word you can combine your scanned images with virtually unlimited text in a variety of fonts to produce exciting, polished pieces useful for letterhead, posters, screensavers etc.

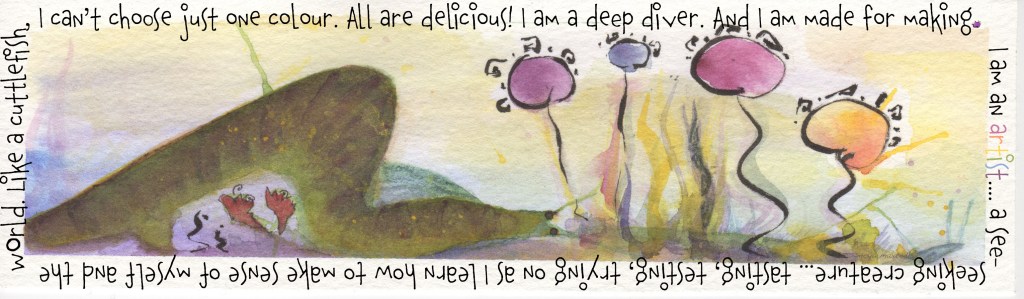

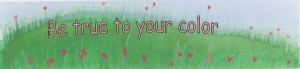

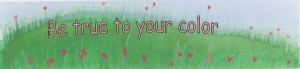

“Be true to your color” is a painting that didn’t make it into the Dark/Light Meditation series but is shown here as an example of how you can scan your painting and then add text. Notice how the background of the painting with text is muted. At the time, my computer graphic skills were fairly limited but I was happy with the result.

Cropping with the computer allows you to select particular areas of an image without harming the original. The flower and it’s shadow at the corner of this painting caught my eye.

Collections

Displays: Your original paintings, once completely dry, may be kept in a folder, bag or sturdy container until you decide what you would like to do with them. Use them as bookmarks for yourself or as gifts. Better yet, why not create a display?

Groupings between two panes of clear glass look impressive. This style of frame may have clips, screws, or a traditional wooden casing to hold the glass in place. Most come in various sizes and can be found at department and specialty stores.

If you’d like to feature an individual piece, consider using a shadowbox frame. Attach sticky tack or several pieces of rolled masking tape (sticky side out) to the back of your painting, and then affix the painting to the back wall of the frame. For added interest, place a related object or photo in one corner, or position and secure (with tape or a glue gun) a few objects along the bottom inside edge. This style of frame lends itself to any number of imaginative arrangements, but remember that the key image, overall, is your painting. Sometimes less is more.

Before committing your originals to a display, it is wise to either photocopy or scan them. Scanning gives you a number of options. Your images can be stored in a file on your computer hard-drive, then burned on a compact disc or printed on paper, and now also stored virtually in ‘the cloud’. Should an original be damaged, lost or eventually belong to someone else, you will at least have a copy for your records and future projects.

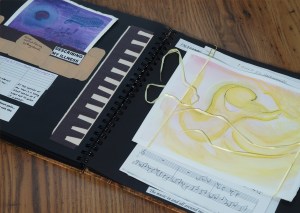

Mixed-Medium Journal: Originals and/or copies of your art can be used to create a mixed-medium journal—a scrapbook that contains visual art and written works.

You already have most of the raw materials needed to make a mixed-medium journal. I advise purchasing a good quality scrapbook, one with a hard cover and acid-free pages. Fill it with your paintings, writings and, if you choose, various other materials. I suggest that you not add too many elements that are not of your own making. This is your book, a unique record of your journey. Let it speak for, and to you. Allow it to reflect the voice of your inner muse.

Give your imagination free reign. Use materials within easy reach. Experiment. Invent. And go with the flow.

The following are examples of things, besides your paintings, that you might choose to include in your mixed-medium journal:

- Torn papers, bits of foil, cloth and other fibers; pressed flowers or leaves

- Your sticky note writings

- Journal entries: original pages or copies of particularly meaningful excerpts

- Magazine text and/or images that appeal to you

- Photographs

- Newspaper clippings

- Memorabilia that hold special meanings

- Projects inspired from either your paintings or written works

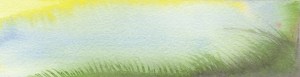

Watching Paint Dry

Paper shrinks and flattens,

colors deepen,

hair and other oddbits lift and peel away.

Some edges sharpen while others become blurred

as colors merge…

small miracles are taking place

in plain view.

“Watching Paint Dry” was written on a sticky note while I sat daydreaming and, literally, watching a few Dark/Light pieces dry. Inspiration may also be gleaned from your journals. Stream-of-thoughts entries provide stimulating images, ideas and language that you can use to create poems.

Return to Seuss

I write what I like

and I like what I write,

in blue on white

and dark on bright.

Color big

and squiggle small,

I like it,

Yes, I like it all!

If Dr. Seuss could see me now

he’d be glad

and he’d be proud.

I’m very merry here today,

in scribble-time I’ve learned to play.

It’s all right,

it is O. K.

The Doctor too had fun this way,

and if the great big kids are true,

they will agree

they like it too.

“Return to Seuss” was part of a stream-of-thoughts journal entry, written a decade before the creation of the poem. The purpose it served at the time was to help me limber up creative muscles. Only recently has it become a piece in it’s own right, one I prepared for Creating Recovery as an example of what you can do with the gems you may find in your journals. It has been altered slightly—a few words were eliminated and punctuation was added but it still resembles my original reverie.

During the process of creating your works, remember to put all preconceived notions aside. This includes your assumptions of what others might think of your art. You are creating your recovery. What could be more beautiful than that? If you can keep this in mind as you create, your art will reflect something intimately meaningful to you. For now, that’s all that matters.

Dearest Child…What you have inside is longing to come out…Why is it you keep forgetting and closing down? It serves no purpose…only keeps you from your work…That which you seek to create already exists. The struggle is not for you to find the words, but to set them free.

~Jan Phillips

When you are ready to share, please do so. By owning your experience, perspectives, and sensibilities you become more fully yourself. The world becomes a better place. And if the life of another person is brightened by your efforts, well, that’s even better.

Beyond Creating Recovery

The painting techniques and approach described earlier are culled from my experience of painting as a tool for healing, and are not intended to take the place of established theories and practices in artistic development. If you are interested in learning more about painting, visual art, and/or creativity and healing, check out the Resources section.